An illustrated record prepared for the silver jubilee year of the British Broadcasting Corporation

1922-1947

Price two shillings

The Place of Broadcasting

foreword taken from a broadcast by sir william haley, director-general of the british broadcasting corporation, on the 14 November, 1947

NO ONE can doubt any longer that Broadcasting has a place. At the end of twenty-five years it has established itself in almost every home in the United Kingdom. It has become part of the fabric of everyday life. It has had an influence on entertainment, on culture, on politics, on social habits, on religion, and on morals. It is the greatest educational force yet known. It has been used in war and in peace as an offensive and as a defensive instrument by great and small Powers…

Any celebration of British Broadcasting would be incomplete without a tribute to Lord Reith. Few men have had the opportunity to render so vital a service to their generation. No man has discharged a great responsibility with more seriousness or with higher purpose…

Broadcasting has its place in the life of nations, of the community, and of the individual. Its use between nations has been a mixture of good and evil. On the debit side there has been — and there still is — the outpouring of propaganda, the ceaseless sapping and erosion of other nations’ beliefs and morale, the misrepresentation and abuse of theoretically friendly Peoples, which some broadcasting systems undertake. On the credit side, there is the power of Broadcasting to pour out over the world a continuous, antiseptic flow of honest, objective, truthful news to which — as Hitler found during the war — the common man cannot permanently be denied access. On the credit side, too, there is the power of Broadcasting, without any unneighbourly purpose, to make the ways of life and thought of different Peoples better known to each other.

Broadcasting is not an end in itself. It will bring about a musically-minded nation only in so far as it gets people to play, and fills the concert halls. Its greatest contribution to culture would be to cause theatres and opera houses to multiply throughout the land. If it cannot give to Literature more readers than it withholds, it will have failed in what should be its true purpose. Its aim must be to make people active not passive, both in the fields of recreation and of public affairs. It will gain, rather than suffer, if it can do any of these things. For it will flourish best when the community flourishes best.

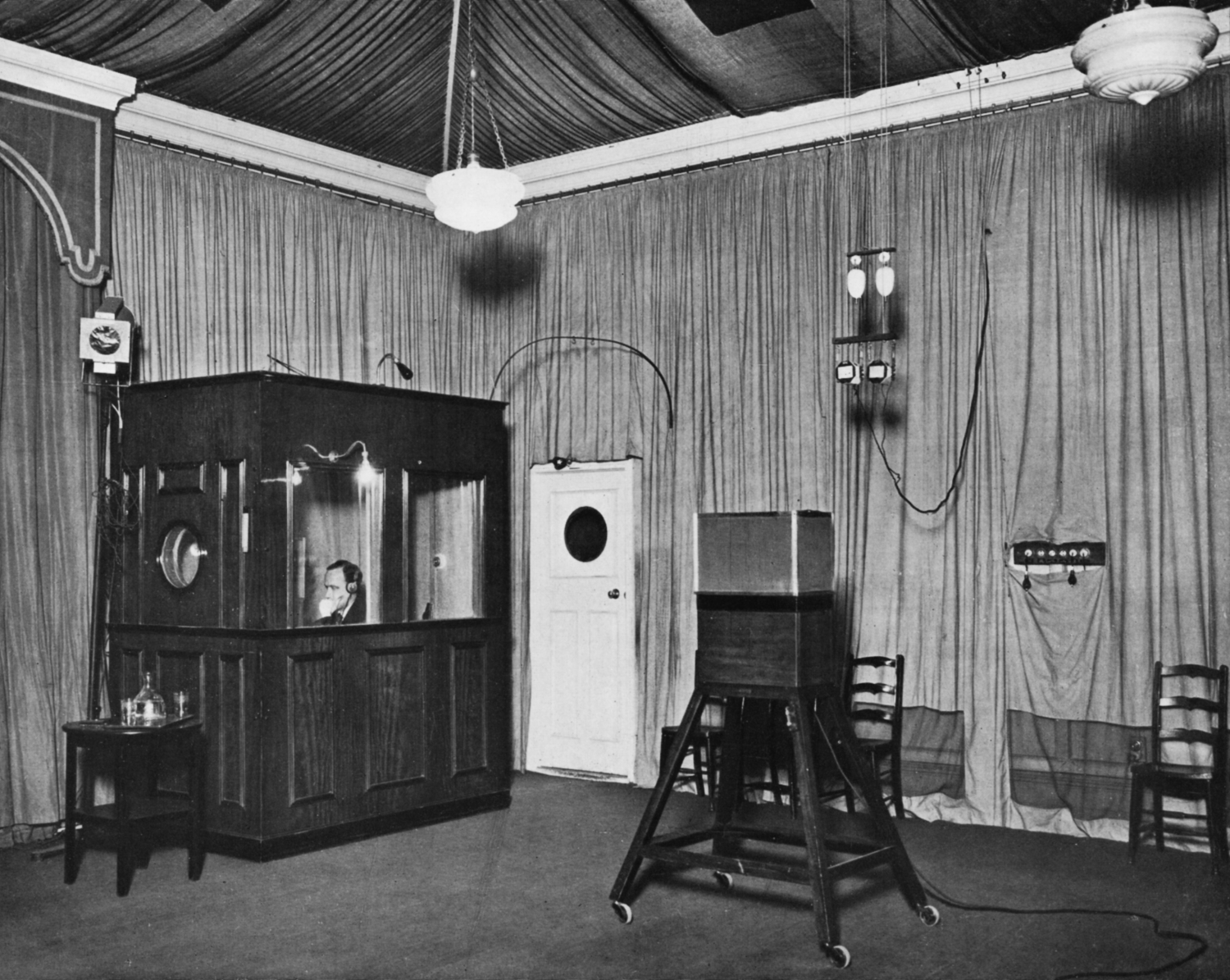

Over the walls and ceilings of the early studios curtains were hung in seven layers, like a Victorian woman’s petticoats. Four tons of material were used to reduce reverberation; the artist’s voice sounded thin and rarefied as though he were on a mountain-top. Microphones, at the start, looked like ordinary telephone receivers mounted on columns later were slung in rubber, boxed in and moved about on heavy trolleys.

BEFORE November, 1922, broadcasting in Britain was carried on by industrial concerns in their research departments and by a few scientific amateurs only. To provide a regular service for a growing body of listeners, the Postmaster-General granted a licence to radio manufacturers to form the British Broadcasting Company, of which Mr J. C. W. Reith was managing director. Programmes began in the evening of 14 November from London (2LO) and next day from Birmingham (5IT), and Manchester (2ZY). Stations in Newcastle, Cardiff, Glasgow, Aberdeen, and Bournemouth were opened within a year. Each used a power of 1½ kilowatts, and could be heard, on crystal set with headphones, at a range of twenty miles. The eight bands of pioneers worked hours without limit, in conditions of severest discomfort. Nevertheless, in a few months, 4½ hours of programmes were transmitted daily without fail to some tens of thousands of listeners. In December, 1922, the News Bulletins were read in London and broadcast simultaneously, by means of connecting land-lines, from all stations. Orchestras were assembled at each station, so far as studio space permitted. Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony was given from London in December, 1922, by seven players! The title of the second talk from 2LO was, somewhat unexpectedly, ‘How to catch a Tiger’. From Covent Garden, in January, 1923, came the first outside broadcast of opera. Plays were put on, though sound effects at first baffled producers. John Henry became the first successful wireless comedian. Relay stations were opened in 1924; next year Daventry (5XX) reached out to the further parts of Britain, carrying an alternative programme, including weather forecasts and gale warnings. When the first BBC gave way in 1926, without change of initials, high sense of service, or guiding spirit, it had won the goodwill of more than two million families.

The picture is of the very earliest days at Marconi House, showing a duet sung by Olive Sturgess and John Huntingdon into separate microphones; that above shows part of the bigger studio at Savoy Hill with soundproof listening cubicle in the corner, and the inevitable carafe of water for libations before the microphone.

ONE afternoon in April, 1924, Sir Walford Davies talked and played to schools. Programmes then normally began later in the day. Two other authorities with the gift of imparting knowledge easily, Sir William Bragg and Sir Oliver Lodge, spoke to schools that spring. In this informal, almost casual way, new horizons were opened, and School Broadcasting, which is now a part of the national system of education, began: bringing outstanding men and women to the microphone, however, is still one of the main things that it seeks to do.

The children listening in the first picture are fathers and mothers now. There are 16,000 listening schools; the number grows each year. With a larger audience has gone increased specialization: ‘Music and Movement’, ‘World History’, English, Geography, Science, and Modern Languages. Schools have their own news commentaries, travel talks, orchestral concerts, a full broadcasting service in miniature, in fact. Mary Somerville, Director of School Broadcasting from 1929-1947, has been its architect and inspiration.

WHEN Parliament decided that the BBC should have a Royal Charter for ten years from 1926, a new organization, operating a modern medium, was lent the dignity and colour of an ancient form. The BBC had its own coat of arms, and flew its own flag. It directed its own activities without interference and controlled its own monies. The Charter called on the BBC to develop broadcasting ‘to the best advantage and in the national interest’. The expanding policy of the years after 1926 showed that the BBC had accepted the full measure of that charge. A high standard of musical performances was set, symphonic and operatic. Plays specially written for broadcasting were encouraged. Men and women distinguished in the Arts and Sciences were invited to the microphone. A parliamentary ban on political controversy at the microphone was raised in 1928. In 1932, the BBC began a service on short waves to the Commonwealth. It was an act of faith and of high technical skill; success was certain after King George V’s Christmas Day broadcast. The metal instrument box had grown new and more powerful wings.

THE broadcasting stream of information and entertainment could not be contained within the first broadcasting headquarters at Savoy Hill. A site for a new building was just above Oxford Circus, at the end of Portland Place. The architect’s problem was to build twenty-two studios, which would be entirely insulated from sounds, and at the same time to provide a large number of day-lit offices. The solution was found in arranging the offices as an outer shell round an inner core of studios, which were planned as a separate building. The outer shell, with its cutaway roof, took on the likeness of a great ship with its prow pointing to the heart of London. Three aerial masts on the roof expressed the function of the new Broadcasting House. Ariel, invisible spirit of the air, was chosen as the personification of broadcasting. In a niche above the main entrance, a sculptured group by Eric Gill showed Prospero, Ariel’s master, sending him out into the world. It was, and is, though no longer a dazzling white among the greys, a twentieth-century building for a twentieth-century institution.

IN THE earliest days ‘balance and control’ were effected by placing the artists relative to the microphone, but the original Control Rooms such as that at Savoy Hill (1) soon became necessary, following improvements in microphones, to accommodate the technicians who controlled the volume and the amplifiers required to feed the programmes to the transmitters. A little later separate rooms (2) with loudspeakers were provided for controlling programmes involving a special knowledge of music.

As the service developed broadcasting stations did not have to rely on their own resources for all their programmes, and many were broadcast simultaneously from a number of transmitters. Thus the additional functions of programme co-ordination and routeing and ‘network’ operation were imposed on the Control Room and these have tended to obscure the original function from which the name derives. The Control Room originally on the top floor of Broadcasting House, London (6) was an example of this phase, but even here separate cubicles were provided for the control of programmes of serious music and also Dramatic Control Rooms (3) for handling complex programmes involving many studios or other sources of material.

Later technical developments have obviated the need for centralizing all the amplifiers and their power supplies in the Control Room, and more recent installations have reverted to the principle of a Control Cubicle associated with each studio and separated from it by a sound-resisting window. The apparatus (4) provides nearly all the facilities available in the earlier dramatic-control rooms, and the Control Cubicles work in conjunction with Continuity Suites, where the programme services are co-ordinated and presented, and a Central Control Room, now devoted almost entirely to the operation of the networks of transmitters, the testing and equalization of the G.P.O. cables between studio centres and transmitting stations, and the handling of all the complicated technical routine inseparable from a large broadcasting organization. An example of this style of Central Control Room is that built in the war in a Variety studio in the sub-basement of Broadcasting House, London (5) to replace the original, too-vulnerable Control Room already mentioned.

This principle has proved so successful that future developments will be basically the same, but a dialling system similar to automatic-telephone practice will replace the present plug-and-socket arrangements for programme selection and distribution.

THE FIRST BBC transmitter was installed in Marconi House, London (1) and was the first of a number of 1-kW transmitters each located near the centre of the town it served. Soon more spacious accommodation was required, and as engineering advances had made it possible to separate the transmitters from the studios, in 1923 the head office and London studios moved to Savoy Hill and in 1925 a 2-kW transmitter was installed on the roof of a shop in Oxford Street (4). This and similar transmitters in larger towns, such as Bournemouth (3), radiated local programmes on medium waves and a big advance was the introduction in 1925 of an additional ‘National’ programme, broadcast by a 25-kW long-wave transmitter at Daventry. The next main development came in 1929 with the opening of Brookman’s Park, the first of the high-power, twin-wave ‘Regional’ stations. These each contained two separate 50-kW transmitters, one for the Regional, the other for the common National programme. These transmitters were of much improved design and were housed in glass-fronted cabinets. Increasing interference from European stations and electrical equipment made it necessary to augment the service in parts of the country. In 1934 a long-wave transmitter of the then unprecedented power of 150-kW at Droitwich took over the broadcasting of the National programme, and additional medium-wave transmitters reinforced the Regional service. Burghead, N. Scotland (2), is typical of these modem broadcasting transmitters, entirely enclosed, remotely controlled and capable of radiating 120-kW.

Series-loaded mast-radiators, which give results comparable to those of higher simple masts, were provided at Start Point in 1937 and Brookmans Park (below) in 1946.

OUTSIDE broadcasting, whose aim is to transport the listener from his hearth, and make him feel that he not only hears but sees what is going on in the world outside, was presented with new opportunities in 1935. Jubilee Year was full of pageantry of sight and sound. On a May morning the commentators from their points of vantage led the listener, with the King and Queen in progress, to their Thanksgiving Service, from Temple Bar up Ludgate Hill and into St Paul’s. Against a background of cheering crowd and clattering escort, they created a sound-picture which rang round the world.

But the ubiquitous ‘O.B.’ in the nineteen-thirties had plenty to do on other and less solemn occasions. Tattoo, launching, horse-race, country festival, after-dinner speech, evensong, ‘Prom.’, hotel danceband, all were outside broadcasts. The public wanted them all and more of them.

Sir Noel Ashbridge, BBC Chief Engineer (crouching by the camera), supervises arrangements for televising the Coronation

WHEN King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in their Coronation Coach reached Hyde Park Corner on 12 May, 1937, they were seen, not only by the throng lining the processional route, but by an army of people scattered over the Home Counties, from Cambridge in the north to Brighton in the south. This was television, bending the resources of a modem phenomenon to the illustration of an ancient ceremony. After experiments had been carried on for some years, the television headquarters of the BBC at Alexandra Palace, on London’s northern heights, settled down to regular programmes on a single standard of 405 lines for two-and-a-half hours every weekday. From the studios came items varying from tap-dancing to grand opera. From a mobile unit came pictures not only of the Coronation but of Wimbledon tennis, the Lord Mayor’s Show, the Cenotaph Ceremony on Armistice Day, and Pet’s Corner at the Zoo. The international crisis of 1938 underlined the actuality possible to television and to no other medium, for viewers in their homes saw Mr Neville Chamberlain stepping from his aircraft at Heston and holding aloft the fluttering piece of paper which he and Hitler had signed at Munich. Although the official estimate of the range of signals was a modest thirty-five to forty miles, there were sets in regular use in the Isle of Wight and Gloucestershire. In the years before the war, the inhabitants of north London came to accept the giant mast on the Palace whose topmost aerial was 600 feet above sea level as a natural part of the landscape, artists became familiar with the awe-inspiring but stimulating conditions of the studio, its glaring lights, roaming cameras and hovering microphones, and viewers grew more appreciative and more critical of a service which was leading the world.

Sound broadcasting, as well as television, played an historic part in the Coronation. The remotest parts of the Empire were able to take part in the ceremony. Fourteen foreign observers broadcast commentaries, each in his own language. This year, 1937, saw a substantial increase in high-power transmitters at Daventry, which resulted in greatly improved reception in most parts of the Empire. Among the visitors to Britain who broadcast from Daventry were an Australian farmhand, a Chinese woman journalist from Singapore, the Governor of an African colony, a schoolgirl from Assam, the Bishop of the Arctic, and a police officer from the West Indies. The daring experiment of 1932 had been fully justified. Empire exchange by radio had become an established and accepted fact and Dominion systems began to re-broadcast BBC programmes. As the international horizon darkened, the Government called on the BBC to institute broadcasts in foreign languages, in the interests of British prestige and influence. The first service was in Arabic, the second was to Latin America in Spanish and Portuguese. After Munich, daily bulletins were broadcast in French, German, and Italian. The aim of all these foreign broadcasts was but to secure a wider audience for a news service which had, in English, a wide reputation for fairness and impartiality.

IN SEPTEMBER, 1939, the BBC went to battle stations. Broadcasting must continue even if the country were dislocated by bombing or invasion. BBC units were therefore scattered. No guidance must be given to enemy aircraft. The transmission system was consequently reorganized overnight, a remarkable technical feat. For months it seemed as if these precautions were unnecessary. But the slow, menacing rhythm of the war mounted. France fell. The bombs came. Queen’s Hall, historic home of the ‘Proms’, was gutted. But the Prom went on, from the Albert Hall, with Sir Henry Wood, undaunted veteran, still on the rostrum (see pictures, above). Broadcasting House, no longer white and gleaming, but battle grey, was thrice hit and the studios in the central tower were wrecked (see photograph of the sixth floor, below). But broadcasting in the thick of the dust and danger, or from remote evacuation points, went on.

NEWS was what listeners of all types and in all countries wanted from the BBC during the war, and never more eagerly than in the early, dark days. At home the nine o’clock bulletin became a ritual. In the Commonwealth they waited for the notes of Big Ben to ring out. News observers, donning khaki, went down to the beaches to interview the mine-disposal squads at their dangerous task (1) or visited the anti-aircraft batteries at their lonely vigil (3). When Rooney Pelletier interviewed young Londoners sheltering in the crypt of St Martin’s-in-the-Fields (4), audiences abroad heard the sounds of actual sirens and of real bombs, the ‘live’ broadcast raised to its peak. Then the U.S.A. became our ally, and the G.I. himself had an opportunity to stand in the shadow of St Paul’s and record his impression of the waste and desolation created by the Luftwaffe (2). Meanwhile Empire troops were pouring into Britain, and cheerful programmes compounded of entertainment and personal messages, such as ‘Song Time in the Laager’ (5), were broadcast from the underground theatre in Piccadilly Circus back to their homelands.

AS THE battlefronts spread across the world, BBC correspondents travelled with the armies, and the opportunities for broadcasting grew. Across the deserts of North Africa, where the tide of success ebbed and flowed, down the Greek defiles, under dive-bombers, over the mountains of Abyssinia, first of the liberated countries, went the man with the microphone, not to give official statements, nor even accounts of strategical situations, but to tell, in his own voice, what he saw, to set the scene of a battle, to catch the mood of the troops, to retail small incidents that brought the war home to the listener. Their vivid accounts were valuable in themselves, and for the experience gained in preparation for sterner tasks to come. On this page a miscellany of pictures recalls those far-flung campaigns on sea, land, and air.

ON D-DAY, 6 June, 1944, War Report was broadcast for the first time in the Home Service after the nine o’clock news. When, eleven months later, the final Report was put out at the moment of final victory in the West, its daily audience had reached a total of between ten and fifteen million listeners. As a programme, it cut across departmental boundaries, involving the close collaboration, both in the field and at Broadcasting House, of newsmen, outside broadcasters, feature writers, and engineers. It was a blend of different skills, combining the situation report, the descriptive despatch, the running commentary, the recording of scenes in sound, and the dramatized documentary. The men who made up the team went through an intensive military training. They were equipped with mobile transmitters for direct speech links. These, as conditions became stabilized, were increased in power, advancing in the wake of the armies. There were mobile recording trucks and vans, such as had been used on other fronts. In addition, BBC engineers had designed portable midget recorders, weighing only forty lb., whose delicate machinery stood up splendidly to the use made of them by correspondents under enemy fire. From the first dramatic moment when London announced ‘And now — over to Normandy’, until the words, ‘It’s just the job’ were spoken by the sergeant who signalled Field-Marshal Montgomery’s orders to the surrendering Germans, War Report, in the Field-Marshal’s own words, ‘made no mean contribution to final victory’.

WITH the coming of war the national broadcasting system which hitherto had addressed for the most part an English-speaking audience at home and in the Empire, developed into a huge, complex, multilingual instrument. That was perhaps the main impact of the war upon the BBC which, at the height of the conflict, was sending out the equivalent of six days’ broadcasting every day, carrying programmes in forty-eight languages and using more than eighty wavelengths for the purpose. Not least among its responsibilities so far as the over-run countries of Europe were concerned, was that of putting the leaders of resistance, whose headquarters was London, in touch with their enslaved peoples in whom a faith in freedom had not died. The heads of Allied Governments established in London made personal contact with the prison house of Europe.

THE story of the BBC’s wartime broadcasts to Europe can be told in four chapters. There was, to begin with, the period when the European Service was groping for an audience, in the days when the remorseless Panzer divisions seemed to have set the seal on the establishment of German tyranny on the Continent. The second phase was the ‘V’ campaign, when, during the summer of 1941, the symbol spread from end to end of the occupied countries. It began simply; Victor Laveleye, Nant Geersens, and other members of the BBC Belgian section, were seeking a way to establish in this clandestine audience, a sign of recognition. They suggested the wearing of a ‘V’. Within a week the R.A.F. were greeted with the sign. It was chalked on walls and roads, tapped out in morse, flashed in lights, not only in Belgium but all over the Continent. ‘Colonel Britton’ became the voice of the ‘V’ sign. The third period was a ‘Go Slow’ campaign, in which, for the ‘V’, the tortoise sign was substituted, designed to keep production down in the mines and factories where workers were forced to labour for Germany. This emblem had great success. The secret newspapers reporting the BBC news grew in numbers and circulation. Arrests, tortures, concentration camps, the firing squad — none of these could stop the listening to London. The final phase came in 1944 when a spokesman (it was ‘Colonel Britton’) gave orders and advice to what were now well-organized resistance groups, whose part in the Allied invasion was a gallant and militarily important one. And when the armies penetrated Italy and Germany, it was discovered that there, too, the BBC had gained and kept large audiences for whom the attraction of knowing the truth had been too strong.

THE postwar pattern of broadcasting for the home listener was soon drawn. Three months after the end of war in Europe, the Home Service, with its six regional variants, and the Light Programme, with a national coverage, were on the air, followed, in a little more than a year, by the unique and daring experiment, the Third Programme. Signs of peace were plentiful. The announcers, who had become so well known, no longer ‘signed’ their reading of news bulletins. Weather forecasts returned. The Symphony Orchestra put on evening dress again for its increasing public performances, and in June, 1947, made a European tour, and was memorably received. Variety put on civilian dress. The radio series, with its catchphrases and foundation characters who week by week became involved in new adventures, became the fashion in comedy entertainment. The serialization of great novels, and particularly those of the Victorian era, was another indication of the listener’s liking for continuity and of his readiness to keep a regular appointment with his radio. Among others who, in the early post-war world, were habitual listeners, were the Services. Forces Educational Broadcasts began in 1945 as a supplement to the Forces’ own educational schemes, and were transmitted to occupying garrison troops overseas as well as to recruits at home. Their success was such that they were continued even after the great bulk of releases had taken place. Radio had made a start on the new problem of post-school education. But the great adventure in Sound broadcasting after the war was the Third Programme, which was tied to no timetable and made no concessions, but drew upon the resources, many of them hidden or neglected, of music, opera, drama, poetry in all parts of the world, to the incalculable enrichment of the serious listener.

REGIONAL broadcasting which has returned since the war with great vigour and vitality, is as old as the BBC.

In the early days local stations were needed not only because transmitters had a limited range, but because there were different traditions and cultures to be expressed regionally. Over twenty years ago, for instance, a station like Manchester was doing as many as thirty hours of its own programmes each week. The next stage came in the early ’thirties, when twin-wave transmitters enabled each part of the United Kingdom to enjoy its own, or the National Programme.

WHEN, in September, 1939, the exigencies of war took from the Regions their own programmes, their identities had become strongly marked. The re-establishment of regional services after the war was generally popular. Since then the songs, plays and talks in the Welsh language, the farming and rural life broadcasts in the West, the free discussions in the Midlands, the humour of Gracie Fields and Wilfred Pickles in the North, the native drama of Ulster, and the national repertoire of Scottish music and poetry have once again flourished on their native soil.

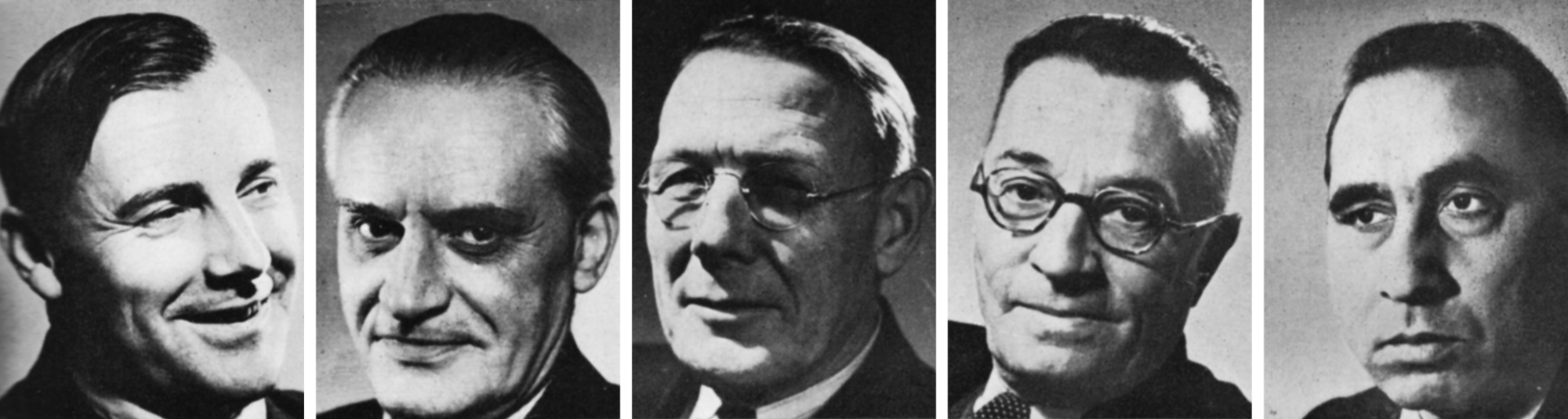

ABOVE: (left to right), Col. Moses from Australia, Prof. Shelley from New Zealand, Howard B. Chase from Canada, Major Caprara from S. Africa, Prof. Bokhari from India

AMONG the many and welcome visitors to the BBC and its studios after the war, some of whom are shown on these pages, two groups may be selected as significant of the BBC’s place as a world institution. In February 1945 the heads of the broadcasting organizations of the four Dominions and All India Radio (as it then was) met at the BBC to consult with each other how to continue their co-operation and develop it. Later in the year representatives of the Dutch people, led by a schoolmaster, brought to London a bronze tablet, showing a kneeling man with his shackled arms above his head listening to the voice of freedom from the west, and this was unveiled in the Council Chamber of Broadcasting House.

THE pageantry and pastime of a great capital city, the flowing patterns of the ballet, the passion and excitement of the play, from Everyman to Eliot, the intimate art of the conjuror, the Parisian vedette and the puppeteer, the complex melodies and rhythms of the modem dance band, the topicalities of‘Picture Page’, the practice of domestic arts, the lively progress and enthusiasms of every sport from horse-racing to darts, all these and many other diversions are now the regular portion of the growing army of viewers. Inside the two studios at Alexandra Palace producers, both veterans from before the war and newcomers, are adding week by week to their knowledge of the new technique. Outside, the cameras range with increasing expertness over the contemporary scene.

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén