Voices of victory

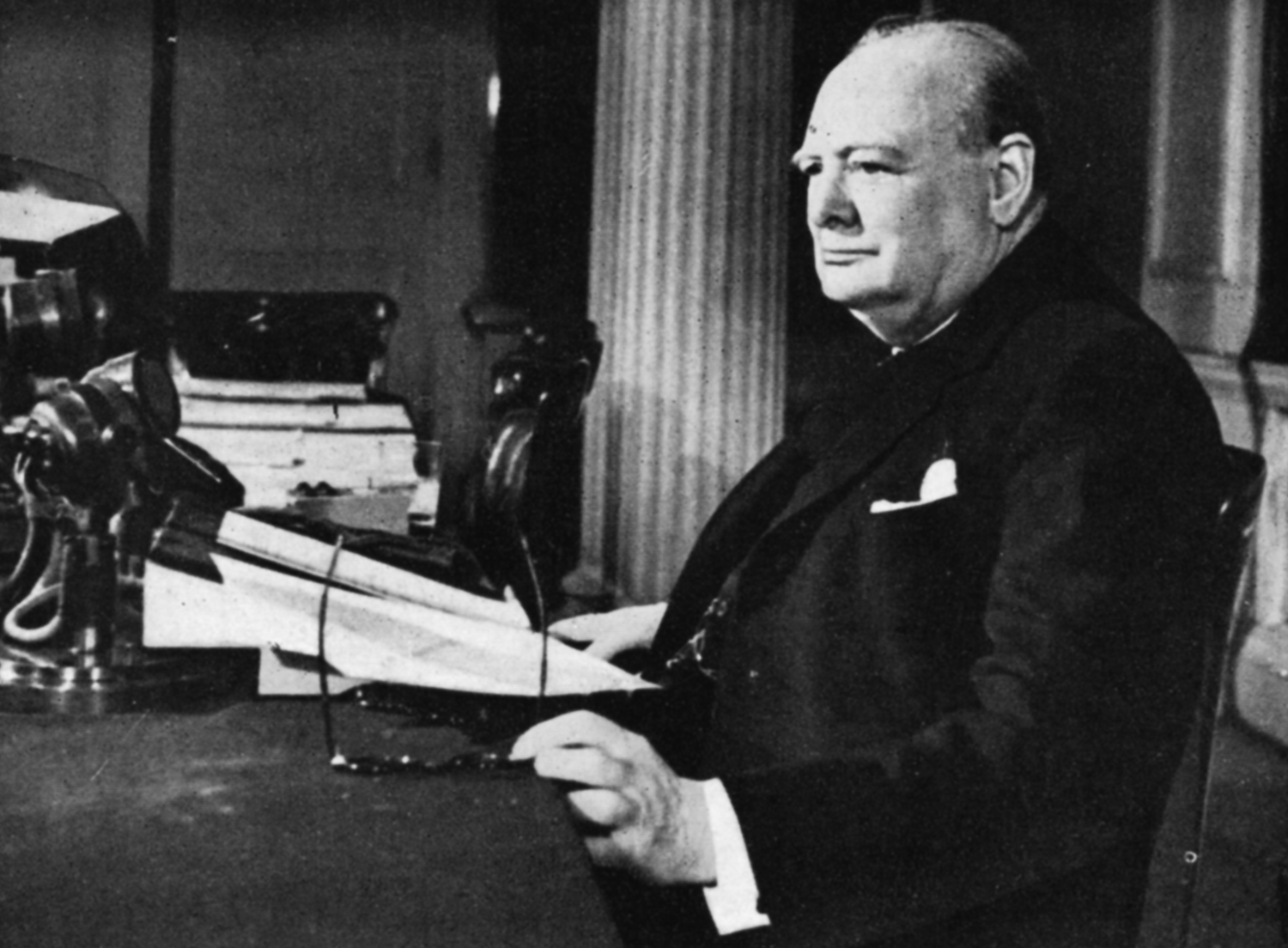

THROUGH the dark and dangerous days, in moods of intense anxiety which swept the whole country, over the weary building-up period, for six winters of blackout, and into the daylight of victory, the listener had at his side a magnificently stimulating companion in Winston Churchill. Never before had the personal magnetism of a wartime Prime Minister been exercised upon an entire democratic nation through the medium of the microphone. As the outstanding military leaders of the Allies emerged, they, too, used broadcasting, and the characteristic tones of Field-Marshal Montgomery in particular became familiar to those who stayed at home as to those who served under him. The BBC, during the war, became more closely linked with the daily lives and habits of the great majority of the British nation than ever before. It was used not only by the statesmen and generals but for a multitude of lesser exhortations, to save salvage, avoid careless talk, cook economically, and shop wisely, and in these campaigns the most popular figures in the world of entertainment were enlisted. Direct assistance to the industrial effort was afforded by the ‘Music while you work’ sessions, designed to lessen strain and relieve monotony in the factories, and entertainments such as ‘Workers’ Playtime’ and ‘Works Wonders’, by enlivening off-duty hours, encouraged work at war speed through the day and night shifts. The BBC Symphony Orchestra, visiting service camps, was greeted with tremendous enthusiasm by its uniformed audiences; from emergency headquarters at Bedford its broadcasts maintained its reputation as a premier instrument of European culture, and such modern and original works as Bartok’s Violin Concerto were performed for the first time.

OVER the whole programme field, the war years represented no standstill, but substantial progress. Special services, designed to meet the needs of the Forces, whose conditions of listening were largely communal, naturally concentrated on light entertainment, and much ingenuity was needed, and found, to keep this fresh and varied. But there were often demands as well for serious music, as already noted, for good drama, for intelligent documentary, and for the exchange of serious thought. The consistent presentation of Saturday Night Theatre at the same weekly time, lifted broadcast plays out of a minority appeal to one in which they rivalled ‘Music Hall’ in popularity, and it was, significantly enough, only a month or two after the war ended that the time was judged ripe to establish a regular series, known as ‘World Theatre’, of plays which had enriched the dramatic heritage of the civilized world. Broadcast ‘features’, attacking in the same spirit of enterprise the problem of telling the real life stories of men and occasions in friendly, dramatized form, also advanced in technique and in popular appeal. The ‘Brains Trust’ had an astonishing success and the original three members, Huxley, Joad and Campbell, with the Question-Master, Donald McCulloch, discovered themselves to be nationally popular personalities, while their example, of spontaneous answers to unseen questions, was followed everywhere, and set a new fashion, which persists to this day, in public meetings of all kinds. ITMA, which in typically British fashion and in a form which could belong only to the microphone, made light of every wartime inconvenience and hardship, established the genial figure of Tommy Handley as Britain’s premier radio comedian. The lights which went up on Broadcasting House on 8 May, 1945, celebrated a victory in which British broadcasting had played a strenuous and faithful part and won its honourable share.