Speaking aloud to every ear

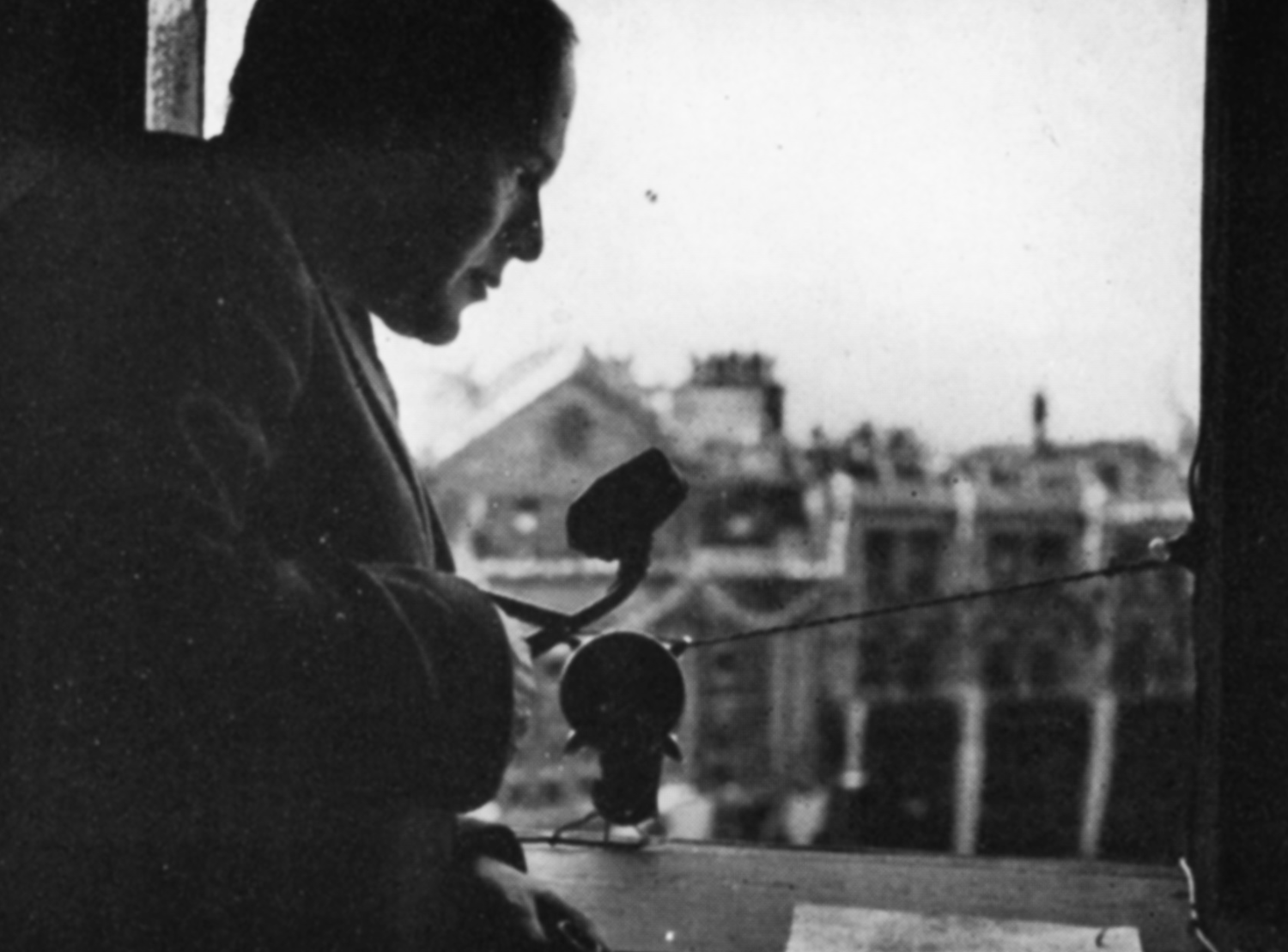

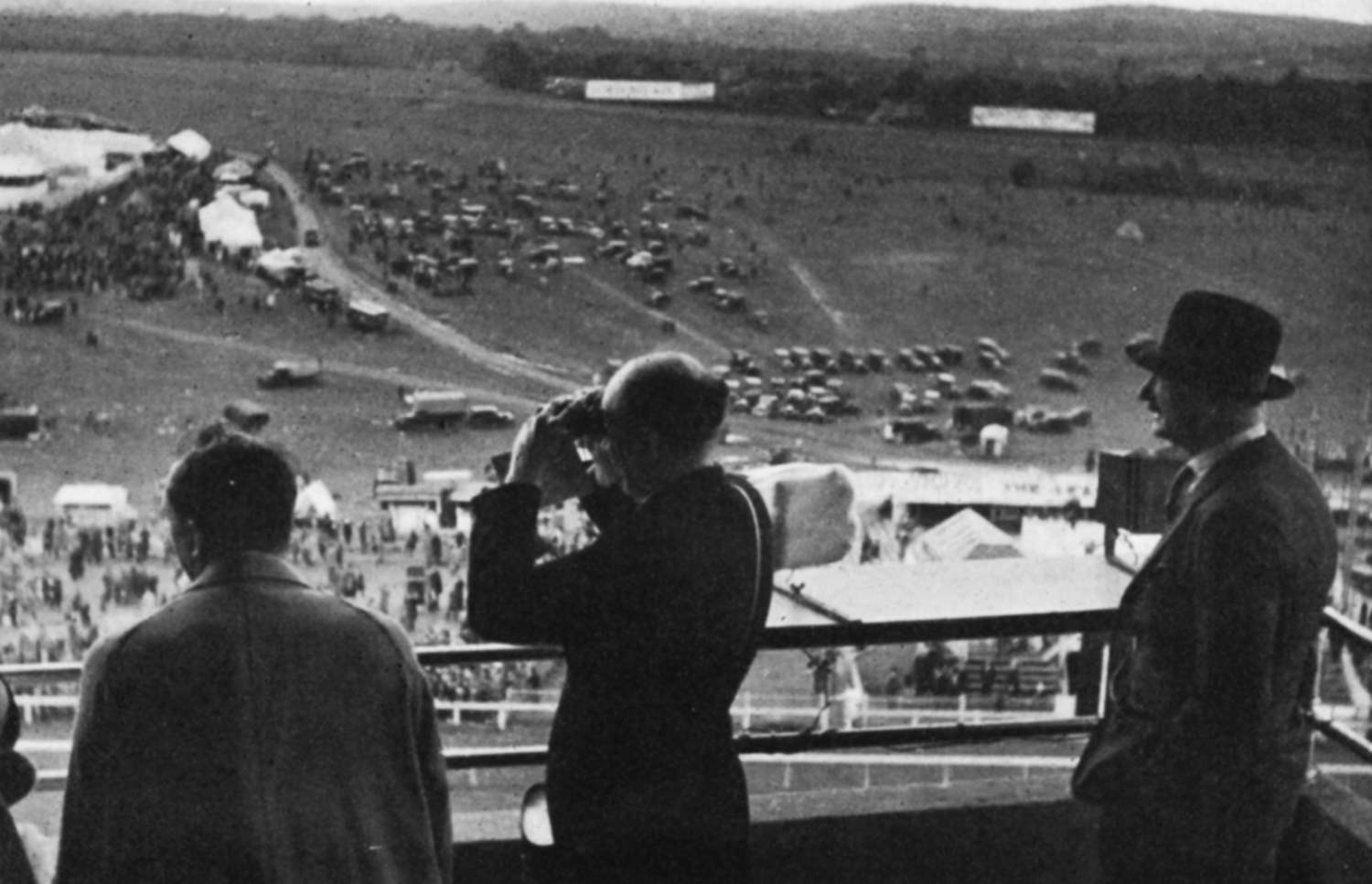

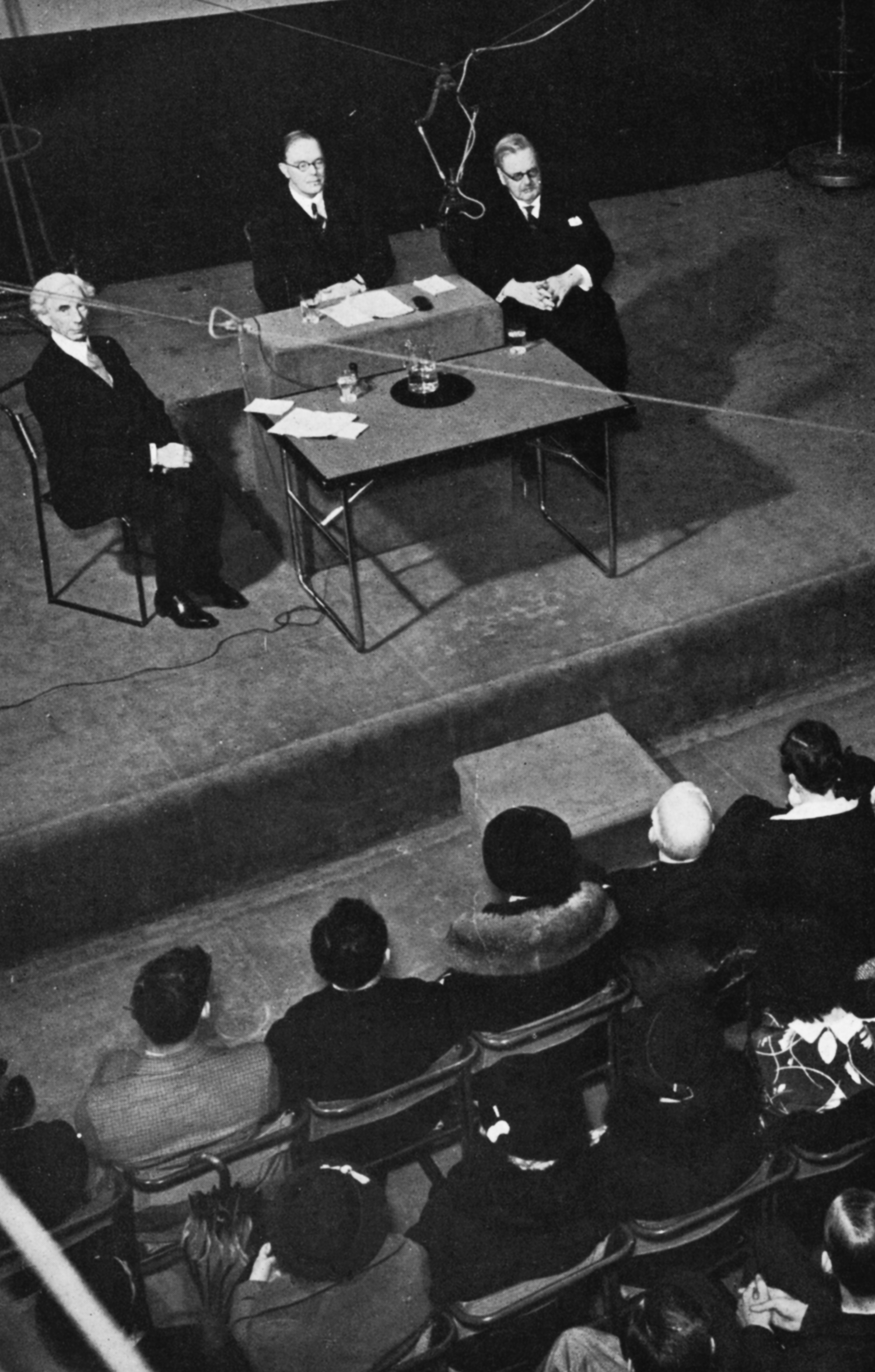

IN THE ’thirties, talks and discussions at the microphone took an increasingly important place in the broadcasting scheme. A number of special services were provided which came to be regarded as a regular and essential commitment — talks to women on domestic subjects, surveys of developments in science, reviews of books, films and plays, sports criticisms, talks for farmers and for gardeners, foreign language courses, talks on musical appreciation and on economic events. The pattern laid down in those years is still followed, to a large extent, today. But in addition, experiments were made, with increasing confidence, in the field of political and social controversy. A series such as ‘Whither Britain?’ brought to the microphone the sharply distinguished viewpoints of such men as H. G. Wells, Winston Churchill, Lloyd George, Bernard Shaw, and Walter Elliott. ‘Time to Spare’ brought vividly home the implications of the great social evil of the time — unemployment, by using the voices of men and women who were themselves out of work. Regional programmes such as ‘Midland Parliament’ (which is still running in 1948), and ‘Northern Cockpit’ presented the local bearing of topics which formed the basis of talk in club and pub and railway carriage up and down the country. The lives and problems of those living outside the United Kingdom were dealt with historically, pictorially, and polemically. The widely divergent opinions which were given expression on the India Bill of 1935 constituted a broadcasting landmark. ‘Unrehearsed Debates’, in which two selected speakers, with a chairman, argued without notes, anticipated the ‘Brains Trust’ technique which later became famous.

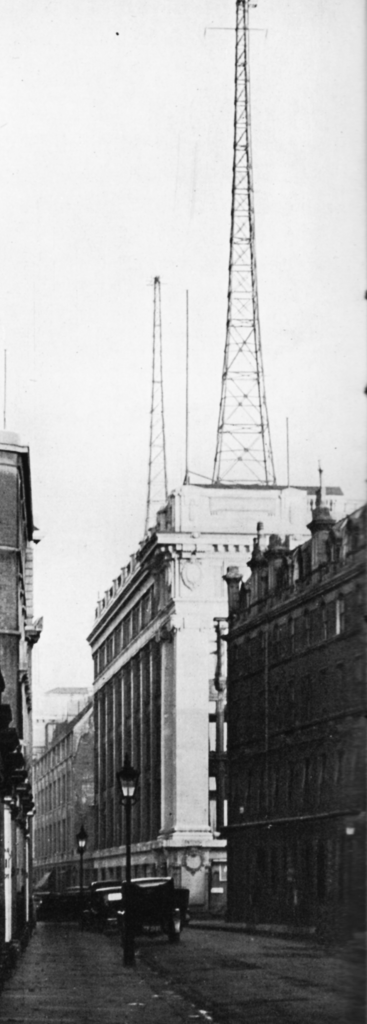

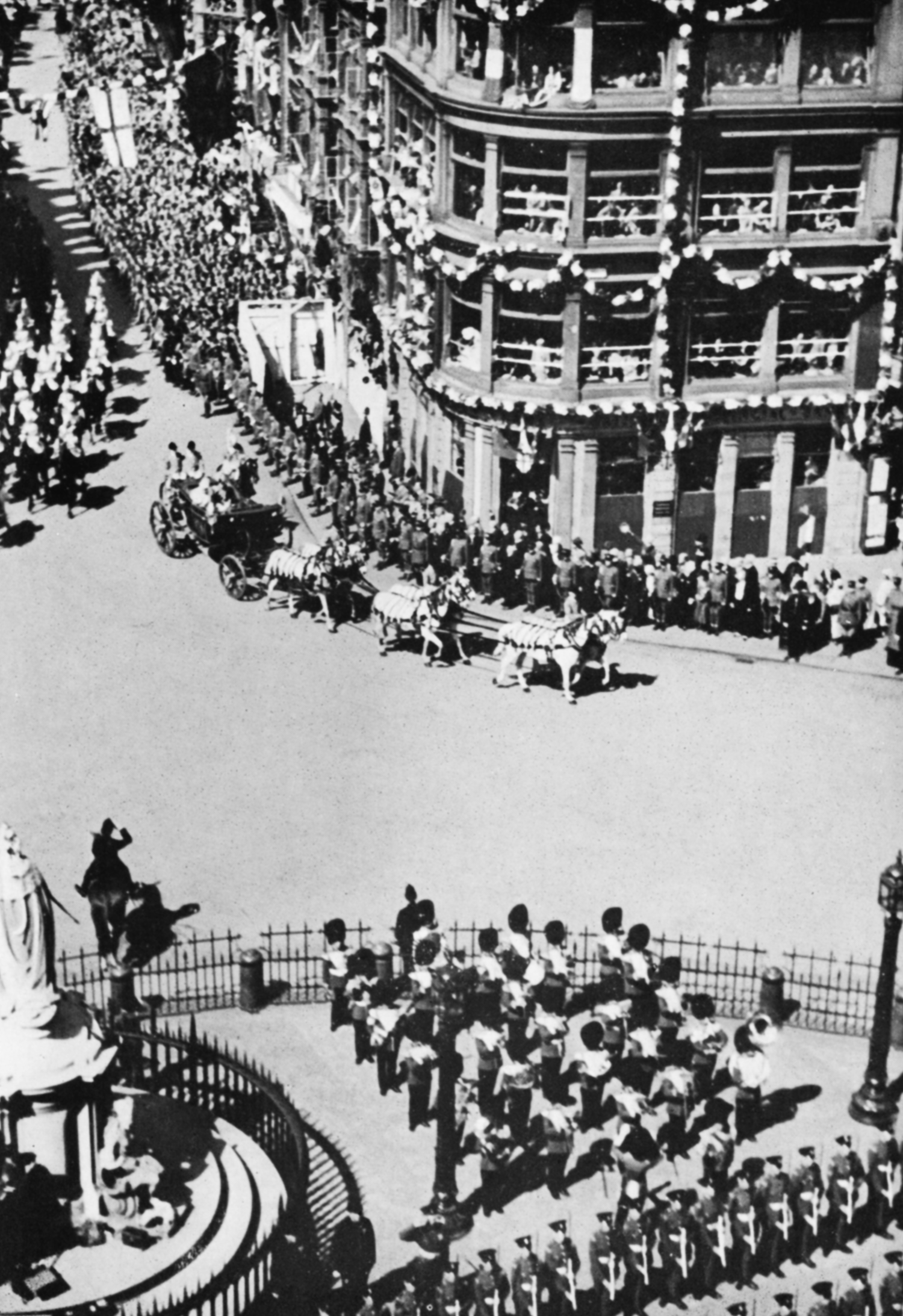

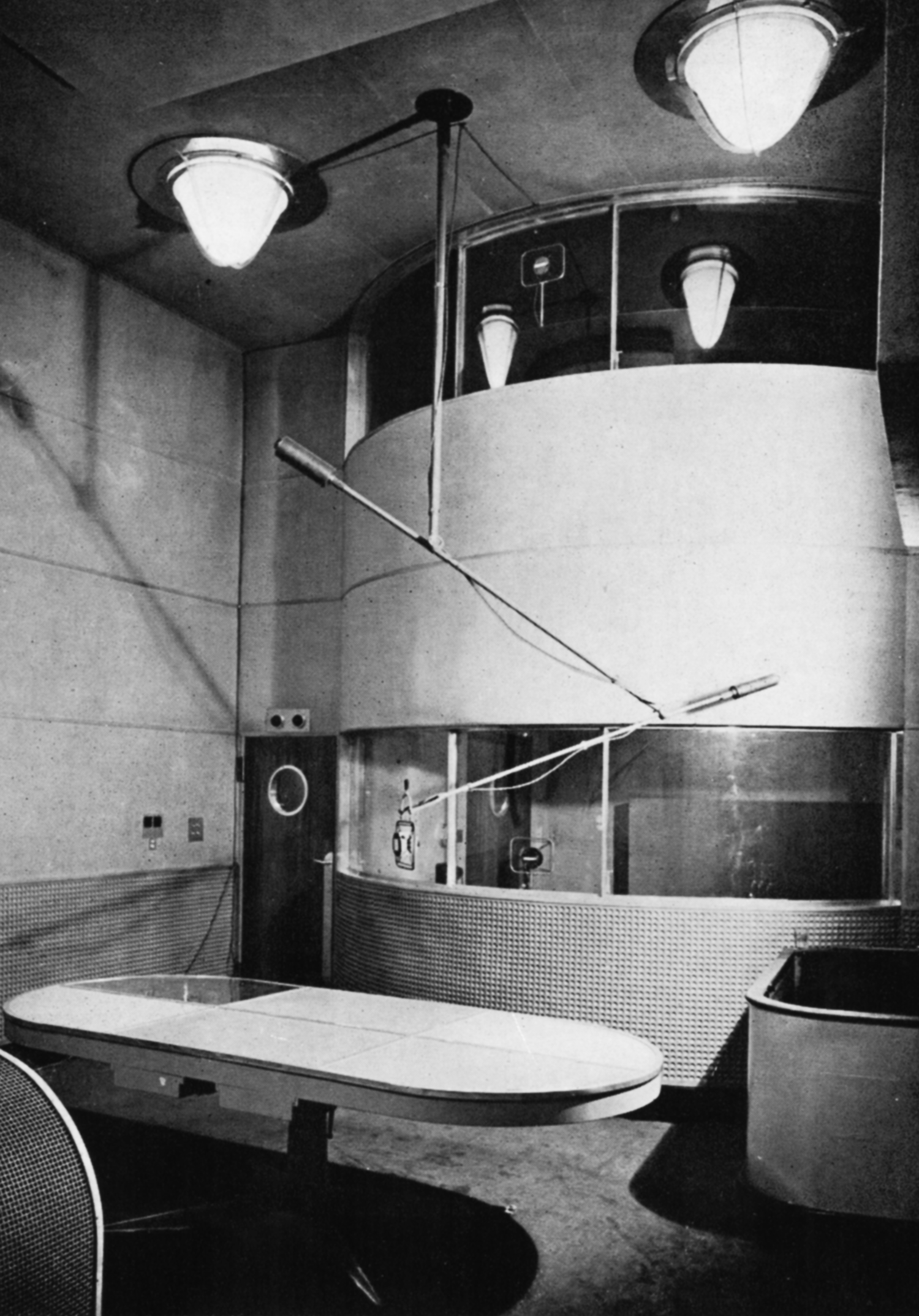

THE year 1936 was one of major importance for British broadcasting, both for the opportunities it provided for the reflection of great national events, the death and funeral of King George V at its beginning, and the abdication of King Edward VIII at its end, and in its domestic history, since after inquiry by Select Committee and discussion by Parliament, the BBC’s Charter was renewed for a further ten years. This, too, was the year in which television opened, the BBC set up a staff training school to train its recruits in the policy and practice of broadcasting, and the BBC inaugurated a Listener Research unit to keep in touch with the habits and taste of its public.

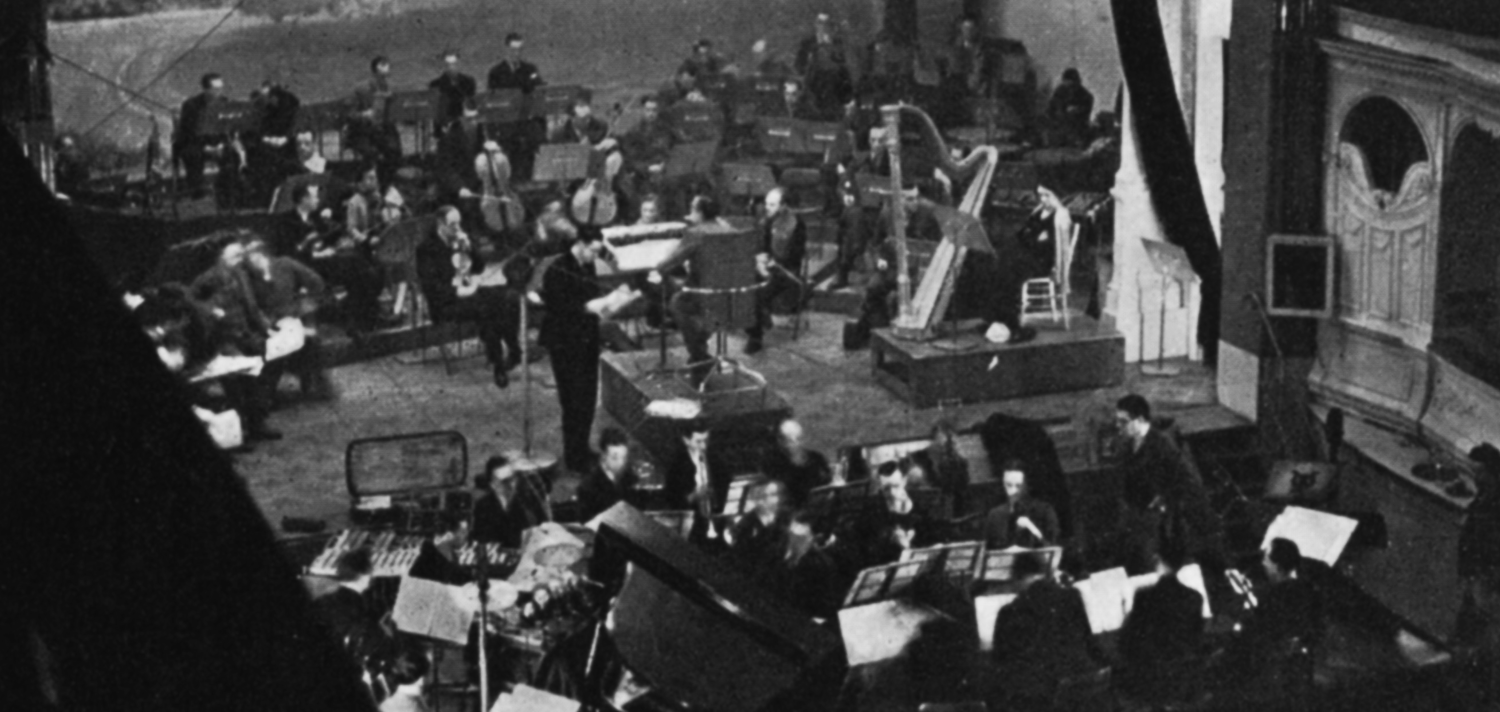

Meanwhile, the body of listeners — by the middle of the decade licences had reached seven million — had come to expect from the BBC a service which touched life at all points and which was a constant source of refreshment and recreation. In music, the Symphony Orchestra gained fresh laurels for studio performances and public concerts alike. In religious broadcasts, the ideal of proclaiming the principles common to all Christian denominations found expression not only in learned addresses, but in the simplicities of the much loved Sunday Epilogue. In entertainment St George’s Hall became the celebrated headquarters of ‘Music Hall’, concert parties, musical potpourri, sophisticated revue, and musical plays, old and new. ‘Bitter Sweet’, with Evelyn Laye, was one of many musical comedies and light operas to run for two hours thus providing an evening’s full and continuous enjoyment.