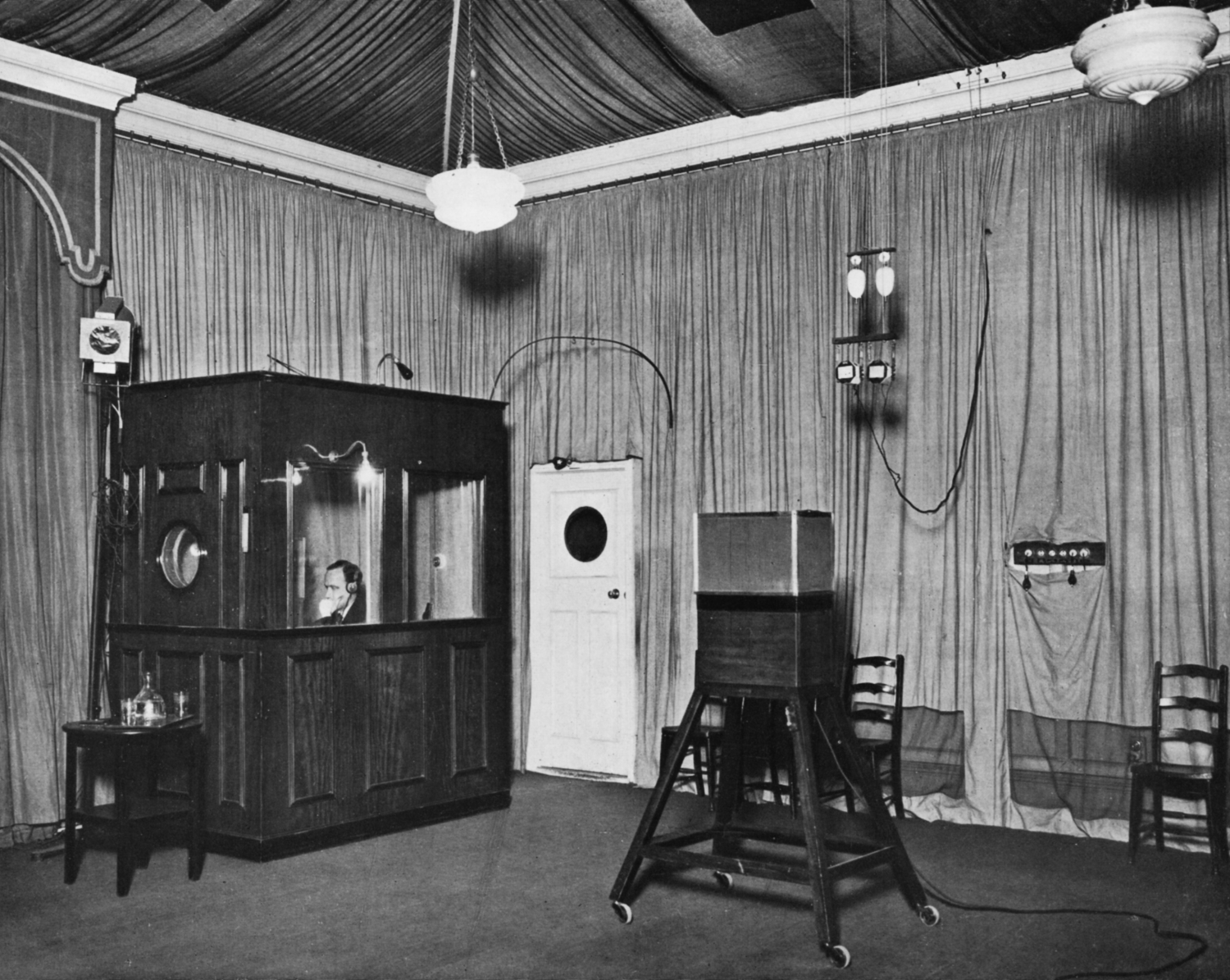

The Place of Broadcasting

foreword taken from a broadcast by sir william haley, director-general of the british broadcasting corporation, on the 14 November, 1947

NO ONE can doubt any longer that Broadcasting has a place. At the end of twenty-five years it has established itself in almost every home in the United Kingdom. It has become part of the fabric of everyday life. It has had an influence on entertainment, on culture, on politics, on social habits, on religion, and on morals. It is the greatest educational force yet known. It has been used in war and in peace as an offensive and as a defensive instrument by great and small Powers…

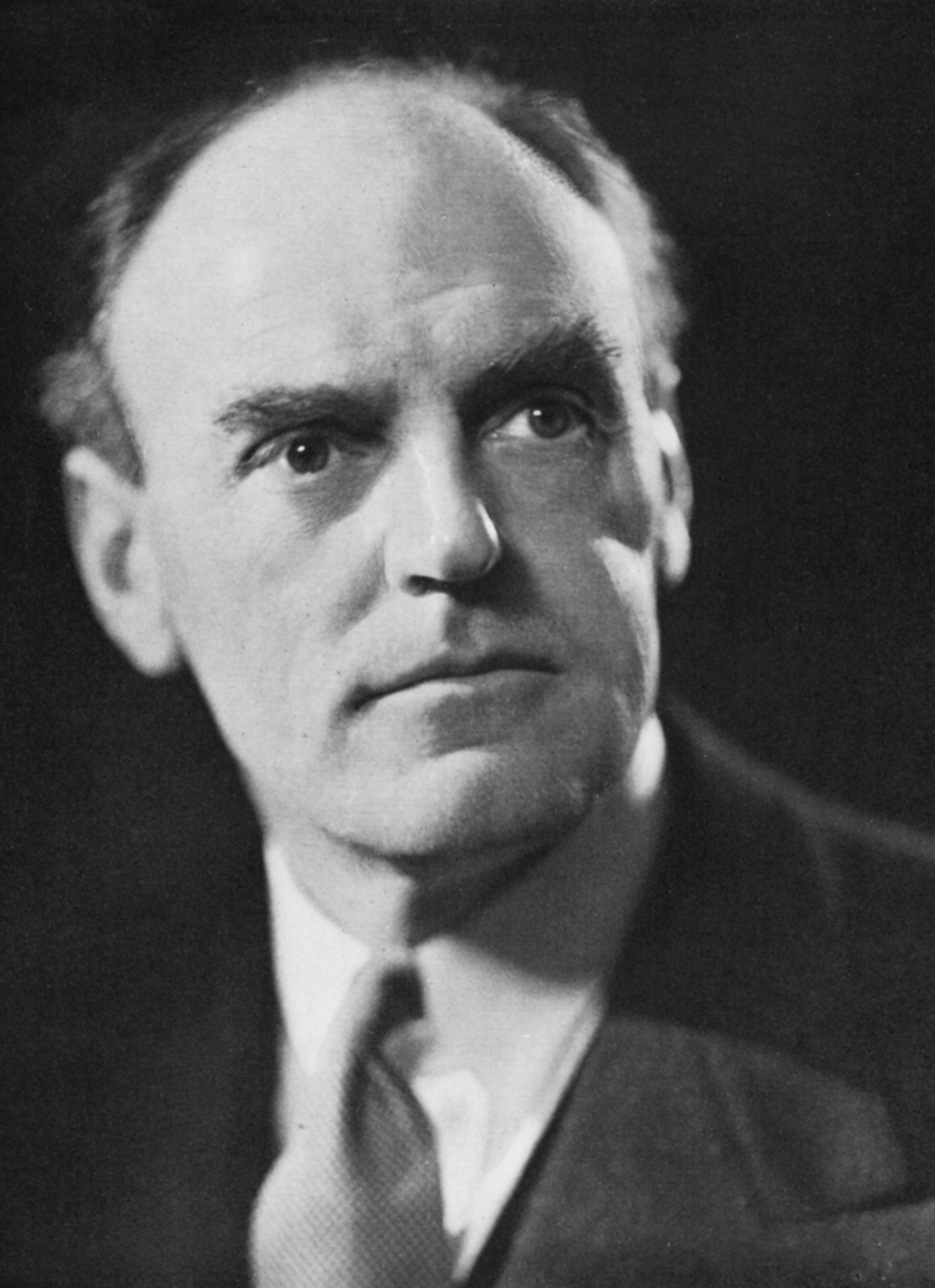

Any celebration of British Broadcasting would be incomplete without a tribute to Lord Reith. Few men have had the opportunity to render so vital a service to their generation. No man has discharged a great responsibility with more seriousness or with higher purpose…

Broadcasting has its place in the life of nations, of the community, and of the individual. Its use between nations has been a mixture of good and evil. On the debit side there has been — and there still is — the outpouring of propaganda, the ceaseless sapping and erosion of other nations’ beliefs and morale, the misrepresentation and abuse of theoretically friendly Peoples, which some broadcasting systems undertake. On the credit side, there is the power of Broadcasting to pour out over the world a continuous, antiseptic flow of honest, objective, truthful news to which — as Hitler found during the war — the common man cannot permanently be denied access. On the credit side, too, there is the power of Broadcasting, without any unneighbourly purpose, to make the ways of life and thought of different Peoples better known to each other.

Broadcasting is not an end in itself. It will bring about a musically-minded nation only in so far as it gets people to play, and fills the concert halls. Its greatest contribution to culture would be to cause theatres and opera houses to multiply throughout the land. If it cannot give to Literature more readers than it withholds, it will have failed in what should be its true purpose. Its aim must be to make people active not passive, both in the fields of recreation and of public affairs. It will gain, rather than suffer, if it can do any of these things. For it will flourish best when the community flourishes best.